Written by Camille Cruse-Marshall for CityLit Project

April 2025 – Submitted June 1, 2025

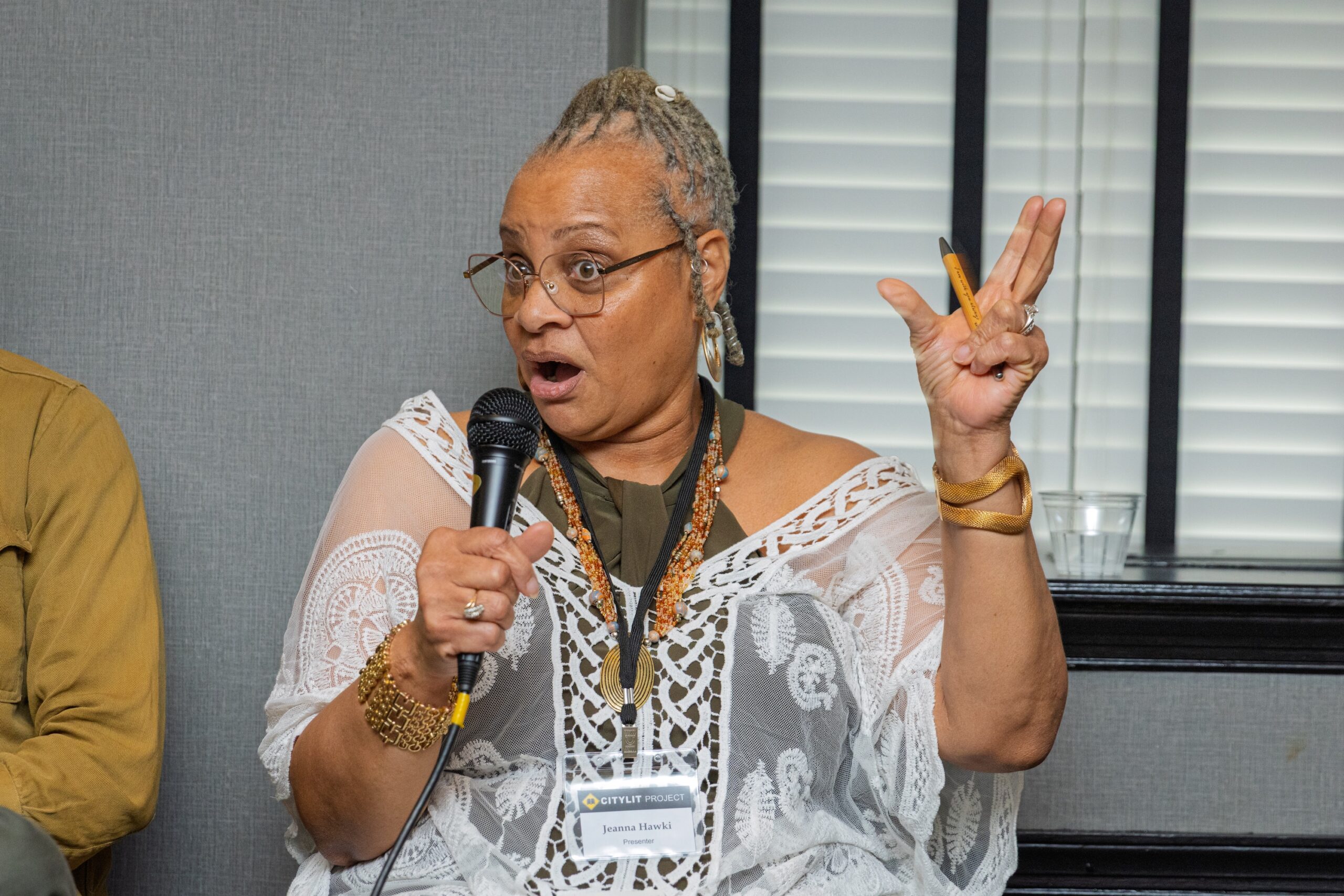

CityLit Project had a busy spring season. Keeping ahead of changes in grants and funding for the arts while producing festivals has been challenging. In April, CityLit held its two-day festival showcasing poets and writers in various seminars and workshops. One standout craft intensive was The Publishing SEEN, moderated by Annie Marhefka from Yellow Arrow Publishing. Marhefka introduced five spirited, unapologetically female-identifying literary award-winning personalities: Sylvia Jones, associate poetry editor from Black Lawrence Press; Dora Malech, editor-in-chief of The Hopkins Review; Sarah Daniels, publisher and executive director of Mason Jar Publishing; Casey Plett, co-founder and publisher of LittlePuss Press; and self-published author, Jeanna Tillery, who pens as J. HawkI (Jay Hawk Eye). The women sat shoulder to shoulder, sharing insights into their personal writing experiences and what their organizations are looking to publish. They also emphasized the importance of the literary community and the fusion of global and local perspectives in publishing. Speaking authentically, the panelists stripped the literary industry down to its bones, then shook the skeletal remains for all to hear the rattling imperfections.

To learn more about each panelist, click here: https://www.citylitproject.org/the-publishing-seen/

Developing and owning a stake in publishing

Annie Marhefka opened up the session by asking panelists to share an origin story of how they found their path to the organization they represent—essentially revealing what led the panelists to develop and own a stake in publishing.

Dora Malech kicked it off by revealing it was “Working with youth literary programs, publishing, and serving on the editorial board of a poetry press” that led her to her role with The Hopkins Review. Malech explained that while working in the Johns Hopkins University Creative Writing Department, “the role of editor-in-chief of the journal came up, and it was a moment to step up as editor, but it was also a moment to re-envision the journal.” Although Malech is from Iowa, she has a passion for the talent coming out of Baltimore in both art and literature. The publication features artwork from local artists on its cover.

Sarah Daniels had no idea what she wanted to do after college. She thought her calling was law school, but then felt, “it was a horrible, horrible idea.” Daniels ended up working for Random House as an executive assistant. After several years in the field, she pivoted into journalism, where she gained a wider perspective on the craft. When Mason Jar Press said they needed fresh ideas, she embraced the opportunity to return to publishing, where she is gleefully in the throes of redeveloping the 10-year-old Baltimore poetry and prose publication.

Jeanna Tillery arrived at self-publishing to satisfy her aspirations as a writer. Says Tillery, “The rejection was exhausting. I felt that I was running out of time. I knew that I wouldn’t live forever, and it could take a small lifetime for an author to get published if you waited for an agent to accept your work and for a publisher to take you seriously.” This provoked a lot of nods from the audience. Tillery went on to say that she had to learn how to promote herself, how to perfect her work, and that it is a 24/7 job while continuing to learn how to grow as a writer.

Casey Plett stood out as the most revolutionary figure in the room. Drawing on her experience as a publicist, Plett realized that there was a void in the publishing industry for transgender writers. While complaining with friends about being sidelined, she and her now-partners, Emily Zhou and Cat Fitzpatrick, decided to be part of a broader solution. “We were waiting for some kind of young piss and vinegar trans literary upstarts to make a press, and we kind of thought we would help them. But we looked around and we didn’t see other presses like that. So we figured we’d start with publishing one book to see how it goes.” This is what led to the founding of LittlePuss Press.

Sylvia Jones, an avid reader and editor, spent her undergraduate years editing for Folio, American University’s literary journal. She then broadened her expertise by reading for Ploughshares, which she continues to do today. During grad school, Jones worked with West French at Bucknell University’s Sandler Center. She credits American University’s faculty and French for exposing her to the vast possibilities of the publishing industry. Jones attended events like AWP Philadelphia. The enthusiasm rang in her voice as she recounted the experience. “There was a sense of real, almost camp-like nostalgia and community. I also met a lot of people and a lot of presses there that I honestly wouldn’t be familiar with…I wouldn’t know about it if that opportunity hadn’t come.” These experiences helped Jones see her potential as a publisher.

Submissions and the pick-me appeal.

“What do you look for in submissions? If you have an example of a piece that came across your desk or laptop, and you thought, I really need to publish this or champion this, what was it that stood out about that piece? Or is there a specific type of vibe or style that your particular press is looking for? We [Yellow Arrow] wish for the writer to tell a story that we feel only this writer could tell,” she continued. “Something so unique to them…that feels so individual and personal but also relatable universally.”

Dora Malech likened The Hopkins Review to a “mixed tape.” If you’re not familiar with the eighties and nineties music scene, it was the hottest way to get introduced to the genre and audience you aspired to impress or relate to. “The journal wants writers who connect with readers, but it also leaves room for passion pieces,” says Malech. “Most issues have a special folio with a theme to it, but we don’t have a theme, and each issue, in a way, we’re trying to include a bunch of different genres, a bunch of different voices, a lot of different representation. Criticism, translation, personal essays, poetry, fiction, visual art, and so the sky’s the limit in that regard.” At The Hopkins Review, editors have conversations while reviewing submissions, asking each other, as Malech puts it, “what popped for you?” While the review aims to be universal, she admits that a consensus is not always a good thing in literature; it’s when they get into a debate that they concur that the piece belongs in their press. Debut writers and short stories help expand the readership, keeping it fresh, relevant, and curious.

Mason Jar Press skews more towards the edgy, radical reader. As Sarah Daniels explains, “We’re looking for work that pushes the boundaries of the genre.” Daniels recently took over the press, and as executive director, she wants to publish work that the reader can’t put down. She reflected on a debut collection of poetry she received from a trans writer that was “so raw, and so real, and so touching, that there was no way that we weren’t going to publish that book.” Daniels disclosed that the press publishes a fraction of its submissions, but that it isn’t due to a lack of interest or reflection on the writer. Says Daniels, “A lot of times if your work is rejected, it is probably very good and very deserving of being published. It’s just that at that moment in time, whoever you had sent it to just didn’t have the capacity to make it happen. When you get a rejection, please don’t take it personally.”

Casey Plett says she and her partners work at a different pace and have very different aesthetics, which she believes works for them. “It means the stuff that we’re drawn to is different. We’re always looking for things that we’re not expecting. We’re looking to be surprised. As a reader, think about when you’ve discovered something awesome and you didn’t expect to enjoy reading it. We are completely willing to be persuaded and willing to be surprised, like, wow, I didn’t think I was gonna read a book like this, but now I did, and I want to publish it.”

Sylvia Jones says, for starters, she prefers to read the bio and cover letter after reading the submission. And as for the type of voice Black Lawrence Press favors, Jones admits she is unable to identify. “I’m not trying to create ambiguity,” says Jones, “but as a poetry reader, I think sometimes resisting what I see or what we can see as patterns could be the most important aspect of autonomy on an aesthetic level, but also trying to anticipate the next thing.” Black Lawrence Press has different tiers of admission as well as open submissions across various categories, and an immigrant fellowship is offered annually. The fellowship allows writers to work alongside the press, giving them a deeper understanding of the publishing process. Black Lawrence Press is small, but Jones makes plain the sacrifices endured by the writers at larger presses. “I’ve heard disappointing stories about not being able to choose your book cover. And I think it’s all about the amount of intimacy you are looking for in your book journey.”

As the conversation turned towards rejection, Marhefka seized the opportunity to address Jeanna Tillery, acknowledging her as someone who, through determination, was able to accomplish her goal of becoming a published author. She asks Tillery to share how she was motivated. With this, Tillery opens a new dialogue and perspective on publishing, believing that there is a rift imposed by academia separating the average reader from the creative writer. Academia creates unnecessary obstacles to obtaining a publishing deal.

“I think that the academic taste is different from just regular people’s taste in books,” says Tillery. “I think that academics expect a different level, maybe a prize-winning level of writing, whereas I just want to tell a story and I want to tell a story that engages my reader. I want to tell a story that engulfs them in my characters and their experiences. One of the points that was made is that you have to query people who are interested in what you write, which is true. And you have to make sure to send them what they’re asking for. And I did.”

Tillery mentioned earlier that she wrote, “query, after query, after query,” until she was worn out.

“I would get the Pulitzer Prize books and read them just to see what it is they’re looking for? And get the New York Times bestsellers list. I would ask, what is this book about? I still don’t know. And so, I think that we may be in two different camps. Maybe that’s where the disconnect is. There is a place for self-published authors to exist. It has to be the best alliteration of what you like to write— you have to make it good. You don’t just put crap out there and expect to do well. But you have to just write for yourself and then find your audience. I had to just find my audience because I found it difficult to conform to what academia expects in that writing.”

Tillery’s insight led to a snowball of support for the self-published journey. Opening up testimony that the role of literary journals and small presses is to bridge the divide between academia and self-publishing. The panel highlighted that the presses foster a more vibrant literary community, building exposure to attract a readership, and submissions are accepted despite having an agent. Hearing this, Tillery remarked, “I wish I knew of all of you when I was looking for a publisher.”

Sylvia Jones reveals her own experience by sharing, “I asked myself, how many poems do I have to get published in this journal for someone to say, hey, we would like to publish your book? I don’t know if it’s bending to the idea of, okay, so maybe enough people will see these logs in this lit journal, or just playing with that clock and that time. [Rejection] is frustrating, and I agree, but I believe that was the role of the literary journal— to bridge the divide between academia and self-publishing on a community scale.

Marhefka agrees by citing the purpose and founding of Yellow Arrow Press, “Yellow Arrow is really focused on emerging writers, which may mean someone who’s never been published before, it may mean a younger writer, or maybe someone who’s switching back to writing or later in life. Our founder, Gwen [Van Velsor], switched to writing midlife and just thought that the literary landscape was overwhelming, frustrating, and confusing, and so she wanted to create these supports and resources for writers. And so we do things a little bit differently, and that we’re not looking for polished pieces. One of the supports that we have is that if they send a poem or a prose piece and we love it and we think there’s potential there, our editorial team works with that person to get it publication-ready, while a lot of other magazines want a perfectly published finished piece.”

Casey Plett says LittlePuss supports the average reader by staying informed of their Goodreads Reviews. “It’s a way for me to kind of be like, okay, are we making things that people out there are connecting with? One of the things we do is consider incomplete manuscripts. It’s like a secret button for us, because there are plenty of great writers out there who have an awesome first bit of a book and not a finished one, then part of what an editor can do is make it a finished one. So that’s actually our secret weapon that I want to offer to all the publishers out there, considering incomplete manuscripts.”

“I often make distinctions between what we do and like big five publishers or the New Yorker or, you know, poetry magazines that have these huge pots of resources,” says Dora Malech. “There is a kind of power to working on a smaller scale and not trying to please everybody, and so I think to find readers that really love you, to find writers that you really love is what I wanted to do.” To drive home this point, Malech read a passage from KillJoy, a submission by A.J. Bermúdez that captured her and became the opening story of this year’s volume. The writer told her that it had been rejected a lot. “So that idea that it just hit the right reader at the right time made me really happy that she found me and I found her in that way.”

The funding and funds challenge.

“In the current climate, what is the impact of what’s happening with your particular organizations and your writers that you’re supporting? Is there anything you’re doing differently to kind of talk through the importance of art right now in this time?” asks Marhefka.

Sylvia Jones – Black Lawrence Press partnered with Independent Publishing Group for distribution. Jones feels that presses have to maneuver and evolve. “I feel as though there’s always gonna be an element of the underground or the mainstream stealing from the underground. And one of the most bittersweet feelings is finding something that you couldn’t say yes to in another magazine that you really like. That’s like the silver lining of a lot of experiences. I’m happy when something has found a home in another journal that you would love to see prosper.”

The panel members voiced support for works published by other presses as a way to mutually survive and also hold down other jobs. Jones is an adjunct professor, and she likens her work in publishing to a labor of love or volunteer work. “I feel like I just wanna make sure the libraries are fun.”

Casey Plett says LittlePuss doesn’t have funders. “We did get a one-time grant this past January from the Mellon Foundation, which kind of saved us because we were changing distributors. One thing that this advantage has given us is that it lets us be nimble, and it means that nobody owns us. It’s something I’m grateful for.” Plett went on to express hope for the industry. “I do have some faith. If you can gather a bunch of people in a room together, because of something artsy, because of something you believe in, things tend to happen. I am fortunate enough that I have been involved in specifically a trans-lit scene for the last decade, and even, not specific trans things I’ve been called to.”

Sarah Daniels advocates that good art raises questions and makes you question things. She says, “That is why I think art can be really dangerous, because it makes you think about things in different ways. And so, it makes sense to me that you would want to cut giving to the arts at this moment in time. So my response to that is to give them the middle finger and keep doing what we’re doing.

“We have our own website,” announces Dora Malech. “We are not on the Hopkins server. When the Department of Justice comes in and is going to mess with Hopkins’ websites, they can’t shut us down. But at the end of the day, JHU is the largest receiver of federal funding.” Despite these concerns, Malech says the magazine remains committed to its mission of championing diverse voices and fostering community through art and literature. A stark demonstration is this year’s journal covers feature filmmaker John Waters’ art. But Malech notes, “it is a very, very tense time in a lot of ways. Students are afraid. They’re afraid of ICE coming to campus, and so, in a way, The Hopkins Review itself is kind of the least of my worries right now in terms of my community. “

The consensus is that everyone hopes to keep publishing a literary collection that their press is known for and support others who may be different but progressive in thought and acceptance.

What’s keeping the panelists committed?

“What’s something exciting, each of you has on the horizon, either individually as a writer or a press?”

Jones is excited to be a reader for her press’s Hudson Prize, Saraband’s Kathryn A. Morton Prize, and Shenandoah’s Academy of Poetry in the Arts annual poetry award. In addition to this, Jones says she’s grateful to be a judge, “tertiary to Diane Seuss,” one of her heroes.

Casey Plett emphasized LittlePuss’ commitment to publishing high-quality, unique work. So unique that their next publication is titled, GenderTrash From Hell, a 90s magazine collection chronicling and catering to a once less targeted transgender community. “There was art, there was poetry, there were essays, there was a review of the Crying Game. There was a lot of articulation about trans culture and movements that existed,” Plett declared.

Jeanna Tillery, exuding focus and purpose, is writing two very different books. Her fifth book, You Never Know What’s Coming, is a narrative about her son’s struggle with a rare disease that affects his brain, thus limiting his ability to move, speak, and live independently.

“I started writing this book in 2017. It has taken a while because it is emotional. I want to give him a voice, and he’s gone through so many things that are interesting that I want to share with his voice.”

Tillery’s sixth book is titled, In a Green Tree. A book she describes as “a dystopian novel, set in the not-too-distant future.”

Tillery credits the inspiration for the story to the Bible. She is just a few chapters in, but the story focuses on recognizing blessings and how to cope with setbacks.

Dora Malech of The Hopkins Review is excited to announce her journal’s new covers. “We publish four issues every year. It’s a quarterly journal, and one of the things that we did with our redesign is have a different colorway every year, so the four covers are a different color. The spines line up, and they make a set together. And with a different visual artist in connection with the city of Baltimore, for all four covers." For the new year, Malech pined over who would get people excited and remind them of that Baltimore connection?” She found the answer by featuring the work of filmmaker John Waters. “I think of flamingos and all the rest of his visual art will be on those four covers this year. That to me is exciting to like put him in this tradition or this lineage, because now the artists who came before, and the artists who come after, hopefully say, this is a series to get excited about. I also got to interview him for this issue.”

Sarah Daniels announced, “We are totally redesigning the journal. So I’m really, really excited about this new relaunch of this product and how it’s going to look.” Mason Jar Press’ “Jarnal” is now accepting submissions.

The session allowed one question from the audience, and it could have sparked another 90-minute session.

The audience member chose to address the largest elephant in the room by asking, “How would you, or how do you think about separating identity from your work, having the freedom to read and write what you want?” She gave further context, referencing an interview she’d seen of a writer who was Black, lesbian, and a Zen priest. She shared, “Thirty minutes into the interview, the interviewer was still talking about her identity.”

Casey Plett said it best: “I can’t count how many times I’ve talked about my writing and just end up being asked about the trans politics of the day, and thinking, I guess you forgot I wrote a book.”

Literary arts is a thread that connects all of the Publishing SEEN panelists. From fractured bones, each building outlets dedicated to giving writers a voice and readers a bag of perspectives from which they can explore, learn, and grow.

Photos of The Publishing SEEN at the CityLit Festival by Mollye Miller Photography.

Camille Cruse is a native Brooklyn, New Yorker. As a kid, Camille always wanted to know the how and the why. Fascinated by history and culture, she spent chunks of her day studying vast traditions of ethnic people. She wanted to know more about what makes people love what they love?

Camille Cruse is a native Brooklyn, New Yorker. As a kid, Camille always wanted to know the how and the why. Fascinated by history and culture, she spent chunks of her day studying vast traditions of ethnic people. She wanted to know more about what makes people love what they love?

Camille’s diverse career in media and entertainment, as a radio and television producer and live events presenter, has always drawn her to stories. Whether its listening to or being apart of the adventure, she makes certain to stay connected to so that she can share the story with others. Bringing stories to light is something that Camille is passionate about.

Jumping into opportunities with both feet is how Camille approaches life. As the launching Senior Writer/Producer for Westwood One/BET Radio Networks, she introduced new strategies for broadening the service, building relationships with PR firms for press junkets, film festivals, red carpet, and radio room coverage. This led to interviewing some of the most notable names in all of entertainment. To name a few, her interviews with Denzel Washington, Robert De Niro, and Aretha Franklin were sourced by radio markets nationally and aired on CBS News outlets.

Now living in Maryland with her family, she enjoys the city’s vibrant energy and great outdoors. Drawing from her childhood journals, she uses her storytelling to reflect on her passion for the cultural experience of city life to nature and outdoor adventure, creating characters that

connect curiosity and wonder to creatures far and wide. Among some of Camille’s greatest adventures is sailing from California to La Paz, Mexico, filming in Costa Rica for National Geographic, sleeping in a Seminole chickee with alligators billowing underneath her, and hiking in Belize with her husband in a newly excavated Mayan cave.

Camille writes at home, in the park, at the bar…in other words, wherever she can. She is currently finishing up a novel, researching her family’s African and Indigenous ancestry, and drafting ideas for podcasts with her long-established partnerships.